YOU MAKE ME FEEL #11: JH PHRYDAS

First published in Entropy Magazine by Gina Abelkop

The book is dedicated both to your mother and to “uppity queers everywhere.” What are the intersections between these two entities? In what ways does your care for both meet and in what ways does it differ?

My mother’s favorite color is blood. This left a profound impact on me as a child: someone who would squeeze a wound to get the dirt out, but also to see the intense beauty of what’s underneath the surface. She would start conversations with strangers in the check out lane in Kroger and dance to anything, including the dishwasher on rinse. Her exuberance protected me as a child fumbling about—confused over everything. The way my body felt in relation to what school taught me, which was also the church, which was also my whole social world. I would get detention for wearing the wrong color sweater. I would learn I was a worthless pansy from other kids, while at home I could burn incense and listen to Leontyne Price and sew and talk with my mom without inhibition. There was an intense comfort in the fact that even her eyes held no judgment.

This book begins with a dream I had about her, the way she still protects me even when we’re in different cities. Her persona an aura that envelops my body, gives a subtle shift to how I see strangers, decisions, daily chores, or having conversations with friends. This aura is one of care that comes from extreme strength: a woman who never finished college but learned from life the importance of compassion. She’s the strongest person I know, and her strength is like pilings holding me up, the sea surging below.

Once I left home, I didn’t find anything close to such care until I fell into San Francisco queer culture. The harshness of living is couched by creative deviance, especially in poorly lit corners of a city at night. The glow of a neon sign retains the feeling of calm my mother carries—that I [hopefully] carry thanks to her. And the bar became a home. And the queers that became my urban family—scared but unafraid to show it—refracted that same couching mentality. I don’t know how to describe it, because even in extreme anxiety brought on by wars, changing urban demographics, joblessness, drinking, premonitions of no future, etc., I felt a bubble where one could breathe. Where I could breathe: locate the anxiety and say: “This is not me.” Although I could trace how it flowed through me.

So, I feel it’s more the care they showed me, rather than my care for them, that I find so inspiring. This book is one attempt at returning that care: a gesture of subtle devotion.

What everyday necessities and unique experiences made up your life during the writing of this book? Are there any books/songs/films/friends/places that made a particular impact on this book?

Tons, and all of them, but I will limit myself to a few.

The project began in 2012 over conversations with Andrea Rexilius, then a faculty member at Naropa University. I was interested in intersubjective theories of resonance and queered/queering phenomenology, especially in the works of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Marina Abramović (I know, so tired!), and Sara Ahmed. My initial intention was for the writing to evoke the socio-political grid in which the queer body is trapped. I ended up reproducing the grid with such rigidity that nothing moved. At one point, I remember Bhanu Kapilplacing her hand on the gridlocked manuscript, saying, “this: but in a different form.” I ended up writing “C♯— B♭” on the first page. Its energy was wrong, so I gave up on the project. It took a year to reenter that space, and only after a daydream, like lightning, when I heard Bhanu’s voice yell: “GORE THE GRID!” And so I did. I took it completely apart, line by line, in order to allow the reader, the ‘I’, to realize a level of mobility.

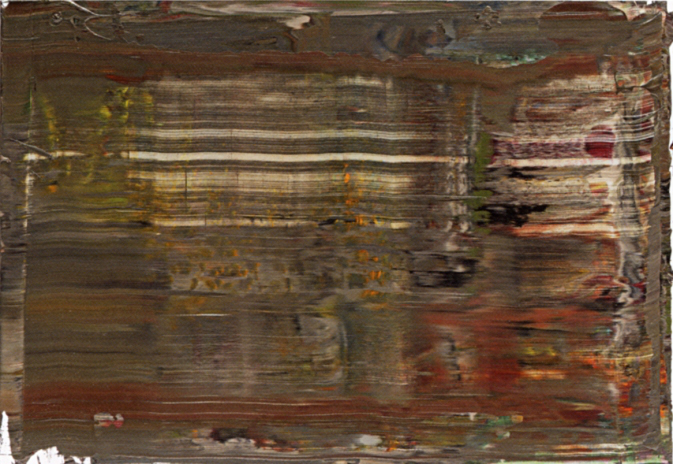

Luckily, there’s an overabundance of time when living in a small mountain town. I don’t feel like I wrote the book; rather, the book built itself from layers of thought, emotion, and anger up in those woods. Each sentence became a color, composed and itemized, and then, during the final months of writing, I would drag my eyes and pen across the entirety of the manuscript—every day from start to finish—as if editing with a comb. If something caught, a strange texture felt against the eyes, the pen, I would slide it away until it stuck somewhere else. Levitations became a sort of Gerhard Richter abstract painting in prose:

I was worried that these initial gestures would not remain within the final draft of the book: that the Richterian durational layering would be lost. Luckily, Timeless Infinite Light helped me retain some palimpsestic legibility within the project design, which can be found on the gridded black pages that start each section.

I also realized, halfway through the project, that in/accessibility is a major concern for me in experimental writing. Two of my dearest friends live in Brooklyn with their two children, and I wanted to write a book that all four of them could read, find a place to enter, find something to grab a hold of. Like The Visitor in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema, I wanted the book to hold everyone in the family differently and pay attention to their specific needs. I wanted that first page to resonate, to take their hands and give at their touch, rather than immediately build an impenetrable wall of words for the sake of intellectual density or value.

Another major influence on the project was my obsession with figuration, specifically, how one figures within a written work. I shied away from characterization in my 20s because of the interest in the blank figure that nonetheless inhabits an embodied existence. This sprung from a desire for self-erasure, and poets like Bhanu Kapil, Claudia Rankine, and the recent work through social media by MCAG have become vital in instructing me in the ways my own status as a white man founded my desire for blankness. I had been conflating sexual desire of the anonymous body with depth of universal feeling. I now realize that the way we figure tells more about us than the figure itself. That, and the figure’s movement through architectural spaces written within the sentence: energized in the act of reading. The interplay of the figure and discursive walls. The white wall that became the monolith of this project dictated every word by the end of the book, each letter a shadow along its pitted surface.

One of my favorite parts of &Now ’15 was your guided activity during which we created clay sculptures as you read aloud to us. What sparked this idea for you, and what are some other ways that you bring physical embodiment to the practice of writing?

Thank you for saying that, because for me, &NOW was a total failure: intellectually, methodologically, and culturally. I left that conference overwhelmed by dejection. I think it stemmed from the fact that the community where I was living and working at the time (in Boulder, CO) was deeply engaged with embodied artistic practice. Especially in the overlap of somatic psychology and experimental writing at Naropa, in which I was intensely immersed. At the conference, it seemed… not very cool. Not flashy enough or something.

But clay and writing intersect at the core of my work, and I wanted to share that with others. This began through a relationship with Michael Franklin, a ceramic artist and therapist at Naropa, who created a writer-in-residency position at the community arts center for me. There, I worked as a literary arts collaborator with a group of adults with disabilities. I was given the opportunity to make art with people whose preferential form of interpersonal communication was not language. Instead, clay, paint, markers, and colored paper acted as conduits for personal expression and connection. The artists I worked with impressed me daily with how nuanced and layered interpersonal experience can be and is, albeit on subtle levels.

I’ll never forget when one of the artists in the studio decided to share, even though he usually remained quiet at the end of class. Holding up a drawing of three blue round objects, he raised his other hand at eye level and began to speak. Moving his fingers along with the sounds coming from his mouth, he created an interplay of movement and tone that captivated us. Even though we could not logically understand the language he spoke, we received knowledge of his being, his experience, his attention, and his desire viscerally: all eyes were on him. Such vibratory extensions of selfhood ‘outside’ of language are held, felt, transmitted in plastic arts, that’s old hat, but for some reason people don’t like to admit similar resonances occur in language, in the written line, as well. It’s the ‘outside’ within language, or, as Lisa Robertson said to me when discussing this work, the embodied “unconscious of language” that I think can be explored through working with clay as if it were writing. Bhanu Kapil was a major influence in this work through her research in interoception, trauma, and somatic writing, and I’m grateful everyday for the chance to have worked with her for two years.

We can learn a lot from decompartmentalizing artistic practices—whose strict boundaries are necessarily kept in place due to the demands of the market and the academy—and thinking of language’s textures, its shapes, its physical presence, its memories, etc. I am currently working on essays around ‘writing as a plastic art,’ and some of them can be found in the Tract/Trace Archive online if one finds this of interest.

Levitations is saturated with color: “pinks and teal globs,” redness, “blue ribbon,” “frothy, brown film,” “rainbow of blood.” What are some of your favorite colors? How does color affect you in your day-to-day life, and how do you hope colors will work in your text?

OMG, this question is huge. I usually prefer earth tones, being a September baby, and my all-time favorite color is beige. But I’m more interested in the referential effects of color in general rather than a color itself. Joseph Albers did his famous color study and wrote a book about how colors shift depending on their context. Although much of his writing leaves color theory flat, I do believe his work pointed towards the importance of examining intersubjectivity within discreet objects, and that pleases me. Because I don’t remember in words but images: I fall in love with the feeling of vivid tones. I had a dream once I went to a textile market and ran my hands along every fabric folded on the tables. My ex-boyfriend chided me, saying: “You’re getting them oily, why are you doing that?” and I answered: “I want to know the texture of each hue in case I go blind.” This may sound trite, but to me was intensely profound.

My boyfriend Stanley Frank—a visual artist and big fan of Dario Argento—has taught me a lot about color in relation to lighting. Coming from a nightlife background, his work with red and blue lighting for drag queer photography and his drawings in colored pencil remind me of the intermittent and mysterious light of the dance floor—the contemporary counterpoint of, say, the green absinthe-sick light of Toulouse-Lautrec. What’s fascinating about black and white film is the use of high contrast colors IRL to create difference nuanced tones in greyscale within a shot. As humans, color is everything. The underneath of a B&W image, bursting with neon color, says so much about our obsession with judgment.

Who are some of your favorite living artists, and why do they make your heart beat faster?

It’s cliché but true: my favorite living artists are my friends. From Mr. David, a fashion designer who left the superficial NYC scene to live in a warehouse in SF and made couture gowns for fellow drag queens, to Judy Bals, who draws insanely funny depictions of everyday life and commonplace sayings, they create art for the love of making their and their friend’s worlds a more beautiful and livable place. Livable, in the sense that global capitalism blah blah blah, you know the story, but it’s true, the world economy in this century is hellbent on erasing individual vibrancy because it’s dangerous to the circuitry. Don’t slow it down! Don’t do something for free! What the hell is wrong with you, not monetizing your work? You’re losing revenue! Aye. My dear friend Helen Hicks told me years ago that, in the future, art will be made for friends by friends, and that nothing else will matter. This goes hand in hand with having to create your own space, your own world, in order to keep going, which is what the middle section of the book gestures towards. I started that section with a quote from James Baldwin, who always says it best: “The place in which I’ll fit will not exist until I make it.”

If your book were a garden, what would you grow there? Which growths would you cultivate, and which would you weed out?

Levitations is totally a garden, and it’s full of rocks and dirt that spills out and gets you dirty when you take it to bed at night. I was a rooftop gardener for awhile in SF, and I love to remember how I would throw slugs off the side of the building and watch them fall 6 stories to the street below. Such a garden is far removed from its originations in the earth, and yet it has what it needs to survive. It just takes extra effort from someone: dedicated to stave off desiccation. I was always terrible at weeding, or hated it at least, since the relativity of the term allows any growing thing to be defined as a weed, as long it’s overabundant and useless. Most plants are useful, some of us just lost that knowledge through our upbringing in neighborhoods far from the dirt. The urban queer nightlife scene was that rooftop garden for myself, and for many others.

If you had to pick 5-10 songs to soundtrack Levitations, which would you choose and why?

Shit. Well, the first section would [unfortunately] be a Shepard tone that doesn’t end. However, each time you get to a page where you enter a room, it would cut to random places in the soundtrack to Tarkovsky’s Stalker. The second section would be a bit more bearable and a lot more fun. I’d throw in some drag, some music my friends make. The third section would be a set of German songs: lower the BPMs, lower the lights, it’s snowing out. The darkness is so thick it touches you. Keep yourself and those you love safe by surrounding yourselves with small worthless objects that you can’t part with. Posters. Bent photographs. Short ceramic vases and a stone given to you at an awkward moment.

In the quest to find out how wide the chasm between our bodies and others is, we look to what folks do with time. All of these songs are ones created to fill the architecture of our lives with sounds that make life worth living. And the chasm between myself and those who perform them shrinks with every listen. Just like reading. Just like drowning in love.

Section 1: Descente

- Shepard tone intermixed with the soundtrack to Tarkovsky’s Stalker by Edward Artemiev.

Section 2: Terroirs

- Sono Come Tu Mi Vuoi by Mina as interpreted by Ambrosia Salad & Stanley Frank.

- Glowing Lady in the Dark by Kallisto D’Amore + Samuelroy.

- Breeze by Dia Dear.

- Lipstique featuring Fauxnique by Silencefiction.

- Riverrun Humbling Allegory by Lauren Bousfield.

Section 2: Manqué

Vier letzte Lieder by Richard Strauss, sung by Jessye Norman.

- Frühling

- September

- Beim Schlafengehen

- Im Abendrot