JH Phrydas

Architextural Attunement: Part One

or

The Lecture Formerly Known as

the Biopolitics of Syntax

The Lecture Formerly Known as

the Biopolitics of Syntax

This lecture is called “Architextural Attunement”—I was originally going to read my masters thesis, “Poetic Attunement and the (Bio)Politics of Syntax,” to you all, but I decided to take a different approach. Instead of just dryly reading an intensely critical paper (as you can imagine by that title, jeez), I’m going to describe to you the journey my research took. I got to talk to a lot of really smart people about super interesting things—and a lot of that is left out of the final paper. So, today, let’s trace the contours and shadings and bumps and valleys of the topographic map I inadvertently began to sketch over the past two years studying body language and interpersonal attunement.

But before we begin, I’d like to start off with an excerpt from a short video: because this is Naropa University, and we love “opening space“ with woo-ey exercise; but also because Maria, who you will soon see, totally gets what I’m about to talk about:

neologism for a perceptual phenomenon characterized as a distinct, pleasurable tingling sensation in the head, scalp, back, or peripheral regions of the body in response to visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, and/or cognitive stimuli.

For some, this is a sensation akin to pure joy: as if someone’s softly stroking your belly as you fall asleep. For others—cold hearted others, I imagine—the sounds of tapping, brushing, steaming, and clicking does nothing. ASMR is, then, controversial in its claim to soothe. But for those that tingle at the sound of crackling cellophane, ASMR can be quite therapeutic. As Wikipedia continues,

A commonly reported stimulus for ASMR is the sound of whispering. As evident on YouTube, a variety of videos and audio recordings involve the creator whispering or communicating with a soft-spoken intonation into a camera or sound recording device. Many role-playing videos and audio recordings also aim to stimulate ASMR. Examples include descriptive sessions, in a style similar to guided imagery, for experiences such as haircuts, visits to a doctor’s office, and ear-cleaning. While these make-believe situations are acted out by the creator, viewers and listeners report an ASMR effect that relieves insomnia, anxiety, or panic attacks.

In the video we just experienced, Maria was role-playing as a cosmetologist. She goes on the talk about our blemishes, how we’ve been taking good care of our hygiene, and then rehydrates our skin with a steamer whose water she infused with chamomile. Now, we can see the steam, but we we cannot “feel” the water droplets on our faces, nor can we “smell” the essential oils Maria so generously used for our “treat-yoself” spa day. Instead, we just have the whispered consonants of her voice and the sound of the machine whirring through our headphones.

What I find exciting is the fact that, underlying the internet sensation of ASMR is the therapeutic use of intonation, rhythm, and cadence of speech to evoke a pleasurable response in the viewer or listener to the point that it can actually relieve stress. Not surprisingly, neuroscientists and sleep specialists are skeptical regarding ASMR’s benefits since adequate and rigorous testing of these phonetic affects has yet to be conducted. However, as I hope to show through this talk, one does not need to “prove” verbally-induced somatic affect; that, in fact, the need for “proof” is, often, a product of a highly structured and vertically-oppressive cultural system whose power is sustained through ideas of “inadequacy” in relation to that which we can or cannot officially know, see, and think.

When I moved to Boulder from San Francisco in the summer of 2012, I was in the middle of writing a short story based on dudes cruising for gay sex. While at UC Berkeley, I shot a photo-essay on an old Twin-Lens Rolleiflex camera that re-presented a number of cruising sites around the Bay Area. Calling this project “Anonymous Portraits,” I made sure to shoot these landscapes without anyone around. A person perusing the show may have just seen black and white photographs of empty parks, rest stops, bathrooms, and windmills. Some, however, would have immediately seen the correlation due to prior experience: a series of well-known hot spots for getting off.

The short story, however, needed to go further than just describing an afternoon cruise in the park. I began asking myself: how could I write this lustful scene in language when, in an actual cruising, you hardly ever speak? The silent ritual of looking for gay sex in public uses other forms of communication: a turn of the head; repeated eye contact; and a shift of a hand towards the thigh that, hopefully, gets that dude on the bench over there interested in you.

This silent and subtle erotic ritual reveals the way nonverbal communication acts as a physically-mediated call and response system towards and away from consummating desire. Words are unnecessary: the body speaks for itself. Muscle, skin, posture, and facial expression combine to produce, extend, and negotiate desire in the hopes of leading to actual, physical touch. Sometimes, speaking can scare your potential suitor away—silence, then, becomes your wing man.

I wanted to write that non-verbal exchange: what happens in that silence. I wanted to find out how one writes what cannot be written.

Jean Genet 1948 © estate brassai rmn

grand palais cliche © Herve Lewandowski

grand palais cliche © Herve Lewandowski

And so I turned to Jean Genet, slutty gay cruiser par excellence and master of gestural writing. One short section from his novel Funeral Rites haunted my own desire to write the gesture of longing. He writes:

My hand was in his, but mine was four inches away from the hand of the image. Although it was impossible for me to dare live such a scene (for nobody–including him–would have understood what my respect meant) I had a right to want to. And whenever I was near an object that he had touched, my hand would move toward it but stay four inches away, so that things, being outlined by my gestures, seemed to be extraordinarily inflated, bristling with invisible rays, or enlarged by their metaphysical double, which I could at last feel with my fingers.

An emergence that begins within the body multiplies. Here, knowledge is immanent, a radiation whose origin is nothing more than the lover’s body and its sculptural position. Notice how this body overflows and becomes transferrable to the objects he touches. The emanation/vibration that makes each object larger than its mass became, for me, not just a symbol but an enaction of that silent, non-verbal space of exchange; felt more than heard, experienced more than understood.

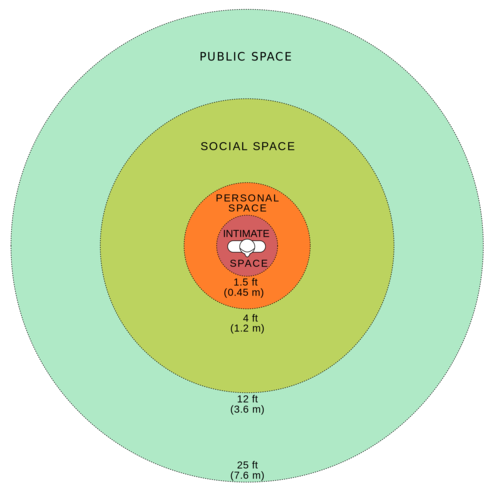

Edward T. Hall's diagram of "proxemics,"

or the study of why we start feeling weird

when people get close to us.

or the study of why we start feeling weird

when people get close to us.

Edward T. Hall, a mid-20th century social anthropologist, attempted to theorize nonverbal behavior. Hall mentions in the beginning of his book The Hidden Dimension (1966) that the study of nonverbal communication began with certain colleagues interested in the “conflict between [two different language systems, the Indo-European and the Eskimos] which produced a revolution concerning the nature of language itself.” This conflict led Hall to speculate that language is, in fact, “a major element in the formation of thought.” He goes on to write that “man’s very perception of the world around him is programmed by the language he speaks, just as a computer is programmed.” Thus, not only do people speak different language, but they also “inhabit different sensory worlds.” Language, as well as culture (since for Hall they are inseparable) are extensions of our physical bodies:

In spite of the fact that cultural systems pattern behavior in radically different ways, they are deeply rooted in biology and physiology. Man is an organism with a wonderful and extraordinary past. He is distinguished from the other animals by virtue of the fact that he has elaborated what I have termed extensions of his organism. By developing his extensions, man has been able to improve or specialize various functions. The computer is an extension of part of the brain, the telephone extends the voice, the wheel extends the legs and feet. Language extends experience in time and space while writing extends language. Man has elaborated his extensions to such a degree that we are apt to forget that his humanness is rooted in his animal nature.

Hall goes on to discuss culture as a hidden extension of the human species that reciprocally interrelates with us and the world we inhabit: “The relationship between man and the cultural dimensions is one in which both man and his environment participate in molding each other.” This molding, according to Hall, takes place in the realm of the nonverbal.

I thought of the cruise. How does the cruise mold those that participate? And how are we all, encompassing all genders, all identities, participating in that nonverbal dance?

Hall focuses on one of five designated layers of nonverbal communication in order to specify and order his observations, which he calls proxemics—or the study of spatial interrelation.

The other four areas, researched by other anthropologists in the last century, are haptics, the study of touch, kinesics, the study of body movement, vocalics, the study of paralanguage elements, and chronemics, the study of temporal interrelation. My interest lay between vocalics and kinesics—between the gesture and the formal qualities of language. Hall, in his book Beyond Culture (1976), has a chapter on rhythm and body movement, in which he discusses “in sync” behavior:

People in interactions either move together (in whole or in part) or they don’t and in failing to do so are disruptive to others around them. Basically, people in interactions move together in a kind of dance, but they are not aware of their synchronous movement and they do it without music or conscious orchestration. Being “in sync” is itself a form of communication.

This nonverbal rhythmic conversation begins, for Hall, early in our lives:

Syncing is panhuman. It appears to be innate, being well established by the second day of life, and may be present as early as the first hour after birth. What is more, stop motion and slow motion studies of newborn children made by Condon and his associates revealed that the newborn infants initially synchronized the movement of their bodies to speech regardless of the language. American children, for example, synched with Chinese just as well as they did with English. From this, it appears that synchrony is perhaps the most basic element of speech and the foundation on which all subsequent speech behavior rests.

Hall goes on to state that this syncing can be thought of as arising when “two nervous systems drive each other.” However, complications may arise when two people from different distinct ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds come together since, according to Hall, our bodies acquire and tune to distinct rhythmic patterns. In fact, Hall states that fear, feelings of hatred, marginalization, and lack of inclusion often result from un-synced rhythmic kinesic patterning. Duh!

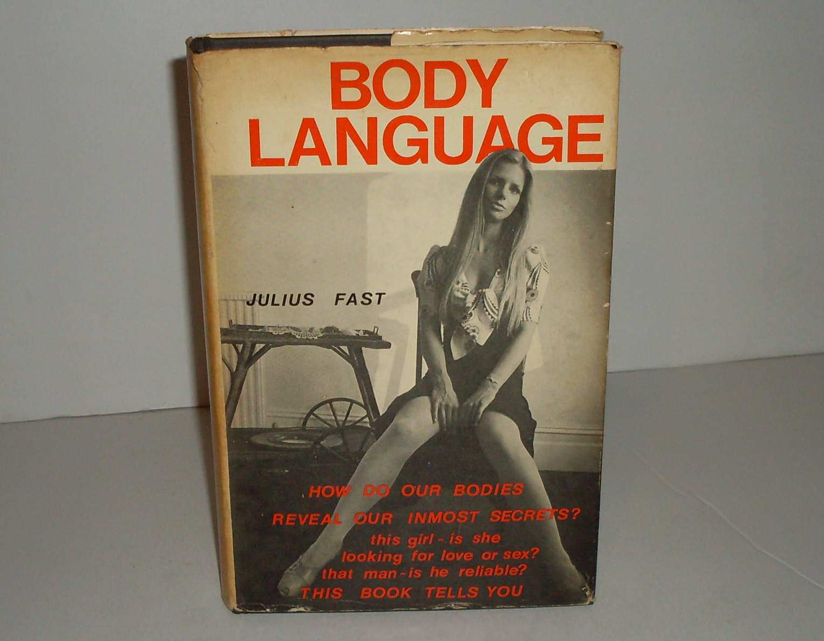

Hall also admits that such avenues of thought can be used for evil as well as good, leading to many books on the subject of “reading” nonverbal communication for financial and institutional gain as well as political control. This became a fad in the 60s and 70s, with writers like Julius Fast taking up Hall’s research as a guidebook for manipulation. Just for context’s sake, let’s take a look at Fast’s best-seller called Body Language (1970).

Cover of Body Language by Julius Fast, 1971.

The title seems innocuous enough. The Daily Mail is quoted on the cover: “shows how our bodies reveal our thoughts; attitudes, and desires.” But take a look at a later printing. Here’s a woman, sitting cross legged. She is surrounded by short questions, ones a purchaser of this book would desperately want to answers to, hemming her in:

Second cover of Body Language by Julius Fast, 1971.

Does her body say that she’s a loose woman?

Does his body say that he’s an easy man to beat

Does your body say that you’re lonely?

Does your body say that you’re hung up?

Does his body say that he’s a manipulator?

Does her body say that she’s a phoney?

Apparently, a young gay man interested in writing a cruising narrative is not the only one interested in nonverbal behavior. Let’s look at another later printing:

Yet another cover.

This girl, is she looking for love or sex?

This man, is he reliable?

The intended audience of this book is pretty apparent, gendered and biased. But what resonates is the main tagline:

How do our bodies reveal our inmost secrets?

Fast’s, as well as Hall’s, utilization of anthropological research depends on the notion that nonverbal communication is, in fact, a language with its own rules, regulations, and interpretations. Someone who reads this book wants to know how to pick up cues, what they mean, in effect, they want to become fluent in meaning, a meaning that most people are ignorant of and a meaning that will help them make money and get laid.

Of more subtle interest is the idea that we are always communicating in excess of ourselves and our intentions, so that someone fluent in body language can learn more about us than we know ourselves: our inmost secrets. And yet, Genet’s “metaphysical double” held sway over my thoughts and my writing. In that one passage, Genet says more than these anthropologists. Immersed in his writing is not just how to read a different language but what it means to be a human, always in movement, consumed with not just desire but beauty, awe, and shame.