JH Phrydas

Notes on Theory, the Body, and Evil

1.

After reading Louis Menand’s article “The de Man Case” in The New Yorker two years ago, I began to wonder about evil and its implications in, theory and, and itstheir implications in contemporary writing practices. Now more than ever, I continue to track such reverberations.

I was brought up in the interstitial space between deconstructionist, post-colonial, and identity theory circles in Berkeley 2002–2006. The turn of the 21st century was ripe with insecurity and mistrust—we were backed into a corner—caught at the ideological edge of worldwide catastrophe and the War on Terror. As the US reinvigorated its stance as an imperialist power, some began to realize that pure literary theory wasn't going to cut it anymore. Emphasis began to be placed on body studies, community/individual politics, and aggression/violence as sites of philosophical, political, and literary praxis.

How much of these popular and academic responses to poetry are affected by ideologies of evil refracted through historical embodiments that make us question language and its conduits? Menand’s essay highlights such questions as he brings up, via book review, the problematic past of critic and deconstructionist Paul de Man: his Nazi leanings, his bigamist lifestyle, his extreme opportunism, and his propensity to lie his way to places of authority. A political and cultural chameleon answering only to himself.

2.

Here’s an experiment: place “Love as a Practice of Freedom” by bell hooks next to Jacques Derrida’s “Mnemosyne.” Which has more authority, power, and value? Now envision the bodies of these two writers next to each other. Which has more authority, power, and value?

Textual vs. social prestige creates a difference in reception of information when the body behind the writing is always at stake. I see contemporary writers attempting to reconfigure the popular understanding of literary criticism, theory, and philosophy when it comes to language. The body, both the one that writes and the one that reads, needs a place, and yet how can we retain a sense of the negative valence that is so vital for illuminating the utilization of language for evil?

People don't like thinking about evil anymore, afraid of essentializing connotations or subtle nods to as well as the resistance towards any sort of reifying, ossifying, or totalizing ideology. In a world of constant emergence, our age is directly linked to these schools of thought and are thus accountable to them—to the extent that we are charged to performwith some sort of transparent critique.

Can we say, in this era, what is evil, and what is not? And how does this relate to resistance within contemporary poetries?

3.

My students say it’s impossible to read a text without thinking of the author. “What’s the point?” they ask, and to a certain extent, they are right. In a world with erasure of privacy and the near-total consummation of every life to the rigors of social media—a move that is self-propelled—and in a time with opacity in the government and continual torture and killing of civilians by drones, what is the point of reading a text simply for metaphor, plot, characterization, or allegory?

It is easier to do with straightforward narrative—the so-called novel, or short story—in which understandable characters live out real-life scenarios, take risks, deal with loss, and find love. The value of these texts arises from empathic resonance: we can understand, we have felt these feelings, we are intrinsically all human, all sharing in a common identity. It is the manipulation of (or resistance to) the intensity of this empathic resonance that gives a readable narrative its power and thus its value. These tales can be separated from the author because it is the tales themselves that hold that which is readable, understandable, and, to a certain extent, pedagogic. Genre fiction, best-selling novels, emotionally-driven short story collections all take their form from the transcription of oral storytelling that underscored the social and religious structuring of our farthest flung ancestorsindigenous peoples. In this way, we can view mainstream writing as a post-cursor to fairytales, origin myths, and epic (i.e., identity/nation-state building) poetries.

Once that understandable space gives way at the edges of what language can do, something else occurs. As we move towards more non-narrative texts and experimental forms, we begin to lose the paradigm through which we affix value: we find ourselves on a mezzanine level, looking down at the conversations occurring in the lobby below.

And yet, many bodies are in the lobby and on the mezzanine simultaneously: the very same body doubled in emanatory being. Not a mirror, but a co-presence through which we find ample room to write and critique the crystalline formations of language as they arise. The light generated by such writing escapes the confines of the building, pouring out of windows to meet the harsh contrast of sunlight in the streets, along open fields. Instead of commingling, these lights cut into matter, chiseling out of prior forms the human condition: bone, blood, muscle, tongue, speech, identity, action.

4.

The contour of a ceramic sculpture has the same force amount of language as a sentence whispered to a lover. Since perception is an act, receiving can be just as active as the passive scan at the edge of a meadow. We receive color, light, and sound through every cell, coursing through us: the world penetrates us incessantly.

There is a tendency to attempt some level of control at this point: by positing consciousness, cognitive thought, modal logics, in effect, as a reaction against the fear of this constant violation of sensory experience. “No, we move information about, we are curators, and thus we control what we are, what we receive and don't receive.” And yet, we cannot help but receive, perceiving vessels without limit.

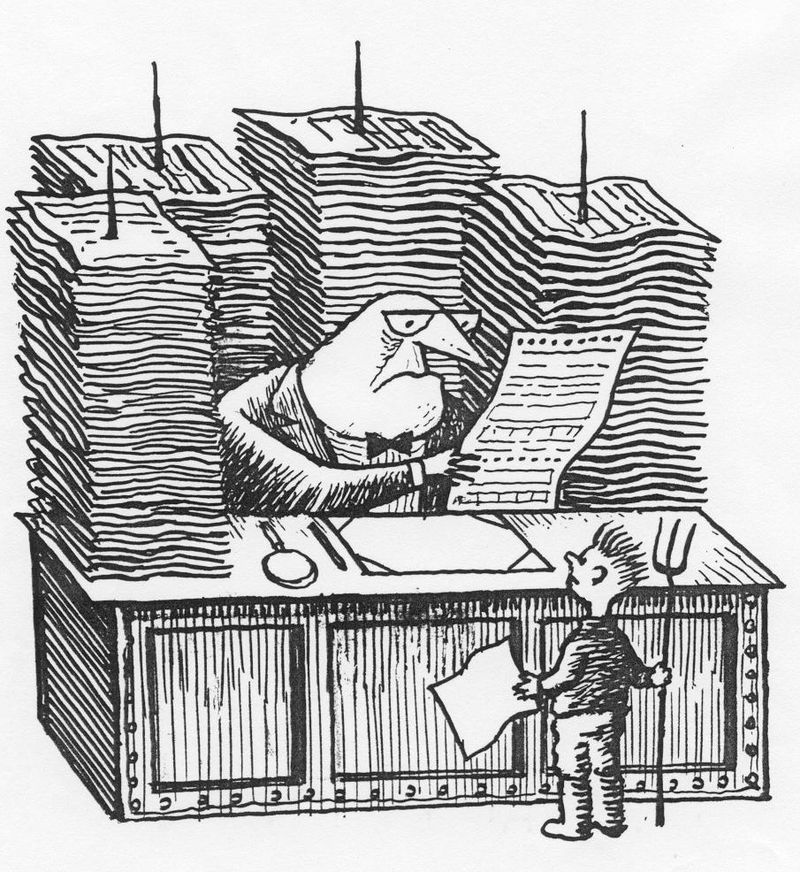

Language, then, becomes the police officer, the border guard, the bureaucrat sitting at theirher desk, surrounded by piles of different colored stamps. We can theorize such figures via indexes, legal hierarchies, commands and allowances: the body as object becomes enmeshed in complicity via total un-avoidance. Kafka knew this and wrote accordingly.

And yet, cops and administrators have nervous systems too.

Those that speak sweet and harshly, that instruct us in the ways of the world, that support and inspire, whose words we read and thereby construct the world: what about their bodies, their actions, theiris histories, sculpted in the light of language and sun? Does it matter who they are and how they live(d)?

And how does this aeffect the way we construct notions of evil through language?

5.

Does language have an unconscious?