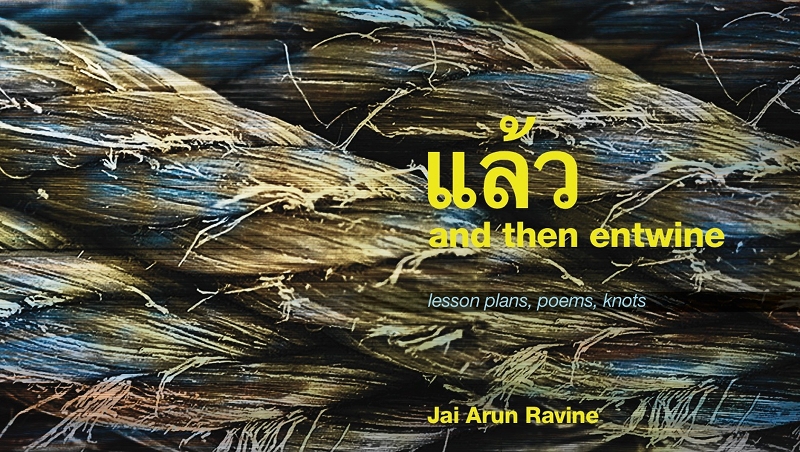

jai arun ravine's AND THEN ENTWINE

First published in Something on Paper #1

“The rope was escape.”

Jai Arun Ravine’s and then entwine is a book of transformation. Slow, methodical, like the tides of the ocean, Ravine writes a textual space that maps the trajectories of the body as immigrant, as biologically mutable, as self-determining. Hir writing boldly and viscerally delves into what it means to translate: topographically, philosophically, and biologically. What is withheld in the space between seeing and knowing? What determines a multivalent body? How does one trace the limits of identity and gender when each is culturally engrained through rigid systems of recognition? What does it mean to cross? Ravine’s narrative is one of becoming: a woman named Gaw, a soon-to-be mother, pulls herself across an ocean westward by means of a rope and in the process “ties knots to mark increments of traversal.” This book is a story of those knots.

“There is a certain tension that allows for movement.”

The landscapes in this book are obscure, place-names remain absent, and yet we are not lost: it is after World War II, and the ocean is Pacific. The topographical indeterminacy of Ravine’s language creates a haze through which Gaw’s moving body radiates like a star tracking in a dark sky. This is not the space of a typical immigrant origin-story. Instead, ze eschews normative border-crossing scripts to write hir own: one mythic, self-determined, tidal. This is prose as experiment, as refraction, as a means to create what does not exist before the utterance: “Gaw searched the geology and tense of what she knew for layers and conjugations of ‘to pull.’ Her discovery became oceanic.” For Ravine, knowledge does not reside in the intellect alone: it can be found in feeling as well as in substance, in body, in earth. Each sentence moves with an undercurrent of these tensions, these multiplying epistemologies, constantly emerging: “She makes a channel and it is the only thing she has desired to know. The light occurs east, and this is her only possible answer…. The question of return blackened and covered the sky.”

“She posed doubtfully before her own history. What tense and geology was this?”

Time flows in this text like a river, like a rope fraying at both ends. We read the trajectory of Gaw’s departure and arrival at a shore far from her homeland, and yet Ravine’s language complicates a simple temporal arc. The past is always occurring, while the future looms unimaginable. Possibly, Ravine offers, in order to locate duration, in order to understand movement, we must look to the body, to the “tiny trespasses” in Gaw’s hands, where “each capillary navigated smaller and smaller tributaries until the threads had to be dissected with a fork.” Does movement necessitate diminishment? What physically happens to the translated body? “What held her was the eventual conclusion, the place where she, future tense, would stop.” Here, the physical and the linguistic converge to hint at a different type of future, one where “the branches of her capillaries continued to widen.” And at that widening, we find: birth.

“To be in control of her own body.”

Hélène Cixous, writing about writing, says: “Writing: as if I had the urge to go on enjoying, to feel full, to push, to feel the force of my muscles, and my harmony, to be pregnant and at the same time to give myself the joys of parturition, the joys of both the mother and the child. To give birth to myself…” Ravine’s text resides in this space of self-birth: writing is a performative act, and as Gaw gives birth to Ram, a child made up of “gears and apparent skeletal architectures,” a new writing also appears. The text begins to shrink and explode over the page, small sentences like refracted memories hover as if dancing. Ram, born of an immigrant woman who “had wanted her child to be a Prince,” acts as both child and text, becoming a multilayered linguistic body.

“[wake] and [cut]”

It is this body, this emergence, which propels the text further than Gaw’s tale ever could. As the form becomes more fluid, as Ram’s body grows, we find paragraphs morphing into stanza, then turning into bubbles containing both Thai and English words. These phrases are incantatory, enacting a mythology of becoming. Ravine hirself refers to this instantiation of mythic etiology in a “Behind the Poetry” essay for Doveglion. Ravine admits: “The project that became and then entwine developed from my need to imagine a historical relationship to Thailand, to invent a past and create a mythology, in order to figure out what that relationship meant to me in the present. I wanted a clear line from A to B to C—from Thailand to the United States to me—so I drew it. I wanted to put that line into my hands.” Here, we get a glimpse of a new origin story that, in the act of writing, becomes a method for mapping what it means to be: a map that always draws us backwards.

“she conjugated her priorities”

Ram’s upbringing becomes one of forms: birth certificates, Thai handwriting exercises, ways to prepare fruit; all of these Ravine reproduces and physically writes over in the text. Like English words answering Thai questions, the child, born in the West, cannot be completely severed from the past, from the homeland Gaw escaped. “The child began to grow a phantom tongue,” dreaming of “kanom, the scent of roots muddied in the riverbank.” Ram, caught in the confluence of multiple cultures and languages, must make a decision and thus begins “backwards in search of the other end of her mother’s lost tongue.”

“and then”

In Thai, the word “gaw,” when added to the past tense, translates as “and then.” Gaw, the immigrant mother, embodies this push towards futurity in Ravine’s text. Ram, the emergent child with phantom tongue, means “workbook.” And then entwine can be read not as a coming-of-age story but as a more fundamental coming to being: a linguistic narrative that traces the trajectory of the emergence of the “I” across seas and over borders. Ravine deftly weaves this narrative between ocean and beach, Gaw and Ram, language and the body, in tension. It is this tension, ze writes, that allows for such movement.